|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

| Last modified on Sat Jul 22 11:30:02 2023 UTC. | Improve this page |

Semaphores are one of the oldest mechanisms introduced by multitasking systems, being used both for managing common resources and synchronisation.

Managing common resources, in its simple form, prevents several threads to concurrently use a shared resource by blocking access of all other threads until the thread that acquired the resource releases it.

Synchronisation is generally required to efficiently implement blocking I/O; when a thread requires some data that is not yet available (for example by performing a read()), it is not efficient to poll until the data becomes available, but it is much better to suspend the thread and arrange for the data producer (usually an ISR) to resume the thread when the data is available.

In µOS++ there are two basic synchronisations mechanisms: semaphores and event flags.

A semaphore is a synchronisation mechanism offered by most multitasking systems. In its simplest form, a semaphore is similar to the real-world traffic light, which blocks access to a segment of road in certain conditions.

The semaphore concept was introduced in 1965 by the Dutch computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra and historically it is said to be inspired by the railway semaphore (the binary semaphore, which controls access to a single resource by bracing the critical section with the P(S) and V(S) primitives).

The concept was later extended by another Dutchman, Carel S. Scholten, to control access to an arbitrary number of resources. In his proposal the semaphore can have an initial value (or count) greater than one (thus the counting semaphore).

Semaphores were originally used to control access to shared resources. However, depending on the application, better mechanisms exist now to manage shared resources, like locks, mutexes, etc. Semaphores are best used to synchronize a thread with an ISR or with another thread (unilateral rendezvous).

There are two types of semaphores: binary and counting.

Note: In µOS++, even if binary and counting semaphores are defined by different classes, the objects created are actually the same, but constructed with different parameters; binary semaphores are in fact counting semaphores with the maximum value set to 1.

Since we mentioned the analogy with the railway system, let’s imagine we have a small train station, with a single platform. The first arriving train enters the station without any restrictions, and stops at the platform. To prevent a second train from entering the station and bumping onto the first, a semaphore is installed at a certain distance before the station. The railway semaphore has a red hand which can be either lowered or raised. Modern semaphores are electric, and also have lights (red and green). After the first train enters the station, the hand is lowered and the light turns red. If a second train arrives, it reads this as “stop” and waits. When the first train leaves the station, the semaphore arm swings up, the light turns green, and the second train can enter the station.

Like a railway semaphore which has two states, a binary semaphore has only two values, 0 or 1. If the value is 0, the resource associated with the semaphore is not available, and whoever needs it, must wait, like the train that stops at a red semaphore. When the resource becomes available, the semaphore is “posted”, allowing the next thread waiting for the semaphore to resume.

Depending on the semaphore usage, it can start either with 0 (when used for synchronisation) or 1 (when used to protect a single shared resource).

What a binary semaphore has in addition to a railway semaphore, is a signalling method (think of this mechanism as a loud horn used to wakeup the sleeping train driver, waiting for the semaphore).

To continue the analogy with the railway system, what if we have a larger train station, with multiple platforms, where many trains can be present at the same time? Well, the solution is similar, but the semaphore logic should keep track of the number of trains in the station, and turn red when all tracks are busy. When one train leaves the station, the semaphore can be turned green, and, if there is a train waiting, it’ll be allowed to enter the station.

A counting semaphore has a counter with a limit, representing the maximum number of available resources.

Depending on the semaphore usage, it usually starts either at 0 (when used for synchronisation) or at the limit (when used to protect a multiple shared resources).

Assuming it starts at zero, with no resources available, the semaphore is “posted” each time a new resource becomes available, which increments the counter. When the maximum is reached, further “posts” will fail and the counter will remain unchanged.

On the other side, when resources need to be consumed, as long as the counter is positive, the requesting thread will be allowed access to the resource, and, at each request, the counter will be decremented.

When the counter reaches 0, no more resources are available, and the requesting thread is suspended, until the semaphore will be posted.

A counting semaphore is used when elements of a resource can be used by more than one thread at the same time. For example, a counting semaphore can be used in the management of a buffer pool.

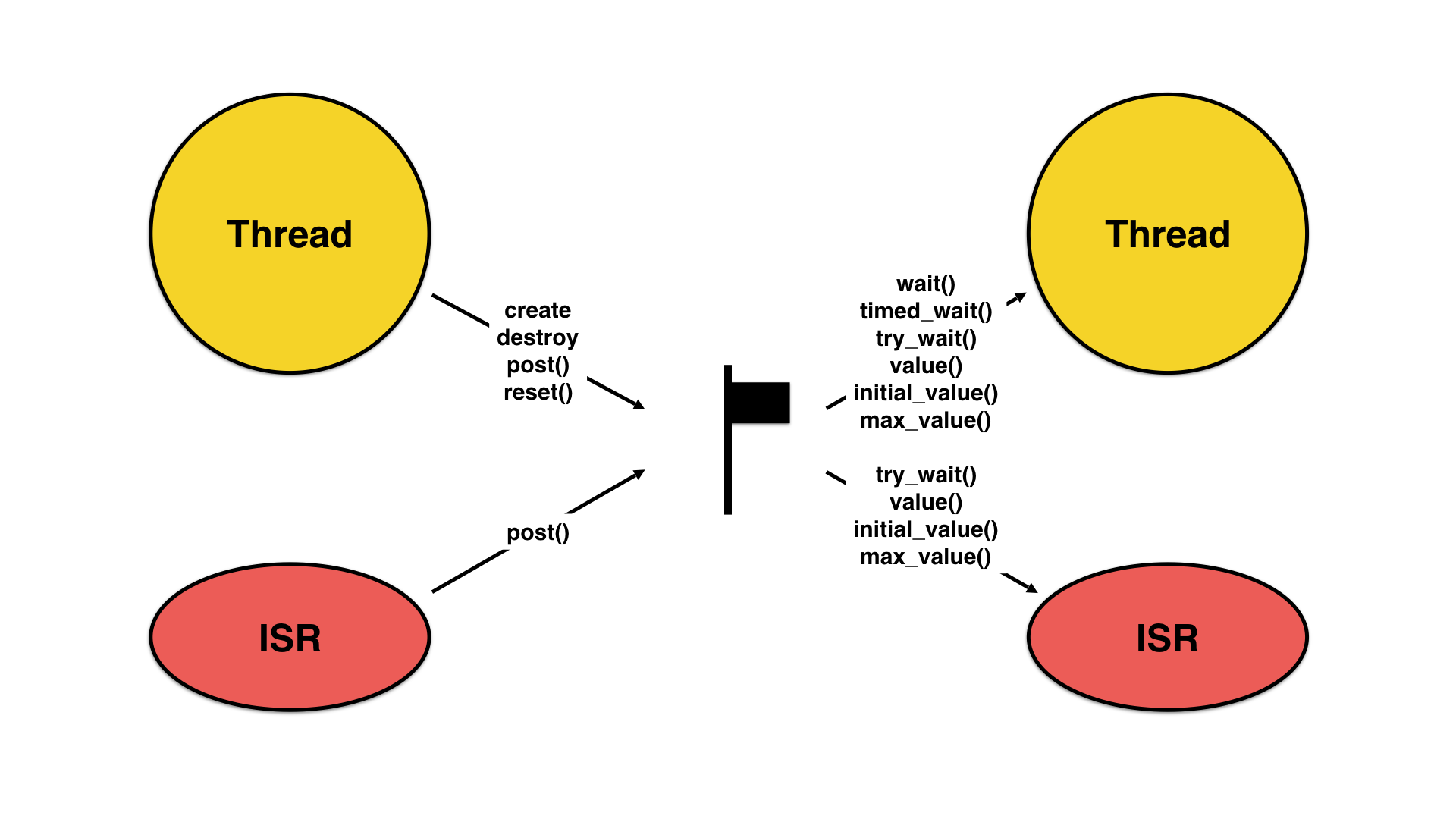

Semaphore services

For convenience reasons, µOS++ has several functions for creating semaphores. Semaphores can be created as local objects on the function stack, or as global objects, semaphores can be binary, or counting, semaphores can be created with default characteristics or with custom attributes, and so on.

When used to synchronise threads with ISRs, the easiest way to access semaphores is when they are created as global objects.

The initial value for the semaphore is typically zero (0), indicating that the event has not yet occurred, or there are no resources. It is possible to initialize the semaphore with a value other than zero, indicating that the semaphore initially contains that number of resources.

In C++, the global semaphores are created and initialised by the global static constructors mechanism.

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 0.

semaphore_binary sb1 { "sb1", 0 };

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// Create a global binary semaphore,

// with the initial count as 1.

semaphore_binary sb2 { "sb2", 1 };

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

semaphore_counting sc1 { "sc1", 7, 0 };

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 7.

semaphore_counting sc2 { "sc2", 7, 7 };

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Not much to do, the semaphores were created by the static

// constructors, before entering main().

// ...

return 0;

}

// All global semaphores are automatically destroyed if os_main() returns.

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

// Global static storage for the semaphore objects instances.

os_semaphore_t sb1;

os_semaphore_t sb2;

os_semaphore_t sc1;

os_semaphore_t sc2;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sb1, "sb1", 0);

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 1.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sb2, "sb2", 1);

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_counting_construct(&sc1, "sc1", 7, 0);

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 7.

os_semaphore_counting_construct(&sc2, "sc2", 7, 7);

// ...

// For completeness, destroy the semaphores.

os_semaphore_destruct(&sb1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sb2);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sc1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sc2);

return 0;

}

In C++, if it is necessary to control the moment when global objects instances are created, it is possible to separately allocate the storage as global variables, then use the placement new operator to initialise them.

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

// Global static storage for the semaphore object instance.

// This storage is set to 0 as any uninitialised variable.

std::aligned_storage<sizeof(semaphore_binary), alignof(semaphore_binary)>::type sb1;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Use placement new, to explicitly call the constructor

// and initialise the semaphore.

// Create a global binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 1.

new (&sb1) semaphore_binary { "sb1", 1 };

// Local static storage for the semaphore object instance.

static std::aligned_storage<sizeof(semaphore_counting), alignof(semaphore_counting)>::type sc1;

// Use placement new, to explicitly call the constructor

// and initialise the semaphore.

// Create a static counting semaphore object instance,

// max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

new (&sc1) semaphore_counting { "sc1", 7, 0 };

// ...

// For completeness, call the semaphores destructors, which for placement new

// is no longer called automatically.

sb1.~semaphore_binary();

sc1.~semaphore_counting();

return 0;

}

Semaphore objects instances can also be created on the local stack, for example on the main thread stack. Just be sure the stack is large enough to store all defined local objects.

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 0.

semaphore_binary sb1 { "sb1", 0 };

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// with the initial count as 1.

semaphore_binary sb2 { "sb2", 1 };

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

semaphore_counting sc1 { "sc1", 7, 0 };

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 7.

semaphore_counting sc2 { "sc2", 7, 7 };

// Beware of local static instances, since they'll use atexit()

// to register the destructor; avoid and prefer placement new, as before.

// static semaphore_binary sb3 { "sb3" };

// ...

// The local semaphores are destroyed automatically before exiting this block.

return 0;

}

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sb1;

// Create a binary semaphore,

// with the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sb1, "sb1", 0);

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sb2;

// Create a binary semaphore,

// with the initial count as 1.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sb2, "sb2", 1);

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sc1;

// Create a counting semaphore,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_counting_construct(&sc1, "sc1", 7, 0);

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sc2;

// Create a counting semaphore,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 7.

os_semaphore_counting_construct(&sc2, "sc2", 7, 7);

// ...

// For completeness, destroy the semaphores.

os_semaphore_destruct(&sb1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sb2);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sc1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sc2);

return 0;

}

For a total control over the semaphore creation (for example to set a custom clock), the semaphore attribute mechanism can be used.

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

semaphore::attribute_binary attr_b1 { 0 };

attr_b1.clock = &rtclock;

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// the initial count as 0.

semaphore sb1 { "sb1", attr_b1 };

semaphore::attribute_counting attr_c2 { 7, 0 };

attr_c2.clock = &rtclock;

// Create a local binary semaphore object instance,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

semaphore sc1 { "sc1", attr_c2 };

// Attributes for a generic counting semaphore, with max 7 items

// and the initial count as 7.

semaphore::attribute attr_g1;

attr_g1.sm_max_value = 7;

attr_g1.sm_initial_value = 7;

attr_g1.clock = &rtclock;

// Create a generic counting semaphore, fully defined by attributes.

semaphore sg1 { "sg1", attr_g1 };

// ...

// The local semaphores and the attributes are destroyed automatically

// before exiting this block.

return 0;

}

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

os_semaphore_attr_t attr_b1;

os_semaphore_attr_binary_init(&attr_b1, 0);

attr_b1.clock = os_clock_get_rtclock();

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sb1;

// Create a binary semaphore,

// with the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_construct(&sb1, "sb1", &attr_b1);

os_semaphore_attr_t attr_c2;

os_semaphore_attr_counting_init(&attr_c2, 7, 0);

attr_c2.clock = os_clock_get_rtclock();

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sc1;

// Create a counting semaphore,

// with max 7 items and the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_construct(&sc1, "sc1", &attr_c2);

os_semaphore_attr_t attr_g1;

os_semaphore_attr_init(&attr_g1);

attr_g1.sm_max_value = 7;

attr_g1.sm_initial_value = 7;

attr_g1.clock = os_clock_get_rtclock();

// Local storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sg1;

// Create a generic counting semaphore, with max 7 items

// and the initial count as 7.

os_semaphore_construct(&sg1, "sg1", &attr_g1);

// ...

// For completeness, destroy the semaphores.

os_semaphore_destruct(&sb1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sc1);

os_semaphore_destruct(&sg1);

return 0;

}

The application programmer can create an unlimited number of semaphores (limited only by the available RAM).

When one resource associated with the semaphore becomes available, the semaphore is notified.

The name post comes from POSIX; other names used are P, signal, release.

result_t res;

res = sem.post();

if (res == result::ok)

{

// The semaphore was posted.

}

else if (res == EGAIN)

{

// The maximum count value was exceeded.

}

A similar example, but written in C:

os_result_t res;

res = os_semaphore_post(&sem);

if (res == os_ok)

{

// The semaphore was posted.

}

else if (res == EGAIN)

{

// The maximum count value was exceeded.

}

When the semaphore is correctly posted, the value is increased and the oldest high priority thread waiting (if any) is added to the READY list, allowing it to acquire the semaphore.

If any of the waiting threads has a higher priority than the currently running thread, µOS++ will run the highest-priority thread made ready by post(). The current thread is suspended until it’ll become the highest-priority thread that is ready to run.

It is perfectly possible to post semaphores from ISRs, generally to synchronise waiting threads with events occurring on interrupts.

To synchronise access to a resource, a thread must invoke the semaphore wait() function.

If the resource is available, in other words if the semaphore was posted and the count value is positive, the count is decremented and the call returns.

If the count value is zero, this means that no more resources are available, and the calling thread will be suspended. The thread will resume either when the semaphore is posted, a timeout occurs, or the thread is interrupted.

Along with the semaphore’s value, µOS++ also keeps track of the threads waiting for the semaphore’s availability (a double linked list, ordered by thread priorities).

result_t res;

res = sem.timed_wait(100); // The timeout is 100 clock ticks.

if (res == result::ok)

{

// The wait ended when the semaphore was posted.

}

else if (res == ETIMEDOUT)

{

// The wait ended due to timeout.

}

else if (res == EINTR)

{

// The wait ended due to an explicit interruption request.

}

A similar example, but written in C:

os_result_t res;

res = os_semaphore_timed_wait(&sem, 100); // The timeout is 100 clock ticks.

if (res == os_ok)

{

// The wait ended when the semaphore was posted.

}

else if (res == ETIMEDOUT)

{

// The wait ended due to timeout.

}

else if (res == EINTR)

{

// The wait ended due to an explicit interruption request.

}

The name wait comes from POSIX; other names used are V, acquire, pend.

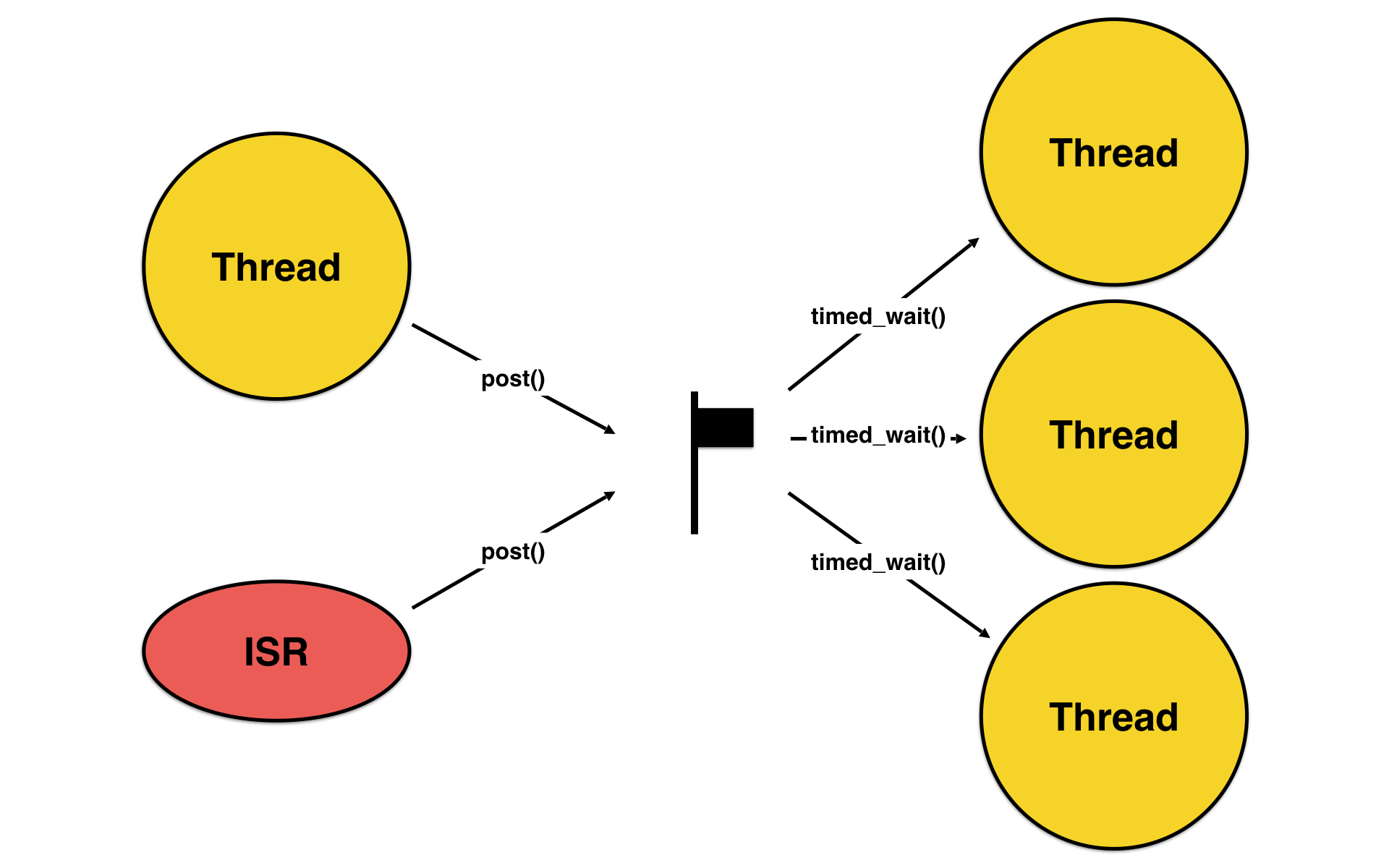

When semaphores are used to manage common resources, it is possible for several threads to wait on the same semaphore, each with its own timeout.

Multiple threads waiting on a semaphore

When the semaphore is posted, µOS++ makes the highest-priority thread waiting on the semaphore ready to run. If at this moment any of the waiting threads has a higher priority than the currently running thread, µOS++ will run all higher-priority threads and only then return to the current thread.

The µOS++ semaphore API basically implements the POSIX semaphores, with several extensions.

The semaphore name is an optional string defined during the semaphore object instance creation. It is generally used to identify the semaphore during debugging sessions.

The C++ API is:

semaphore_binary sem { "sem", 0 };

const char* name = sem.name();

The C API is:

os_semaphore_t sem;

os_semaphore_construct(&sem, "sem", 0 };

const char* name = os_semaphore_get_name(&sem);

The semaphore value is the instantaneous counter value, if positive, or 0 if the semaphore exhausted its resources and there are threads waiting for it.

The C++ API is:

std::size_t value = sem.value();

The C API is:

size_t value = os_semaphore_get_value(&sem);

The semaphore maximum value is a constant value set at semaphore creation, representing the total number of resources associated with the semaphore. For binary semaphores, these functions return 1.

The C++ API is:

std::size_t value = sem.max_value();

The C API is:

size_t value = os_semaphore_get_max_value(&sem);

The semaphore initial value is a constant value set at semaphore creation, representing the number of initial resources associated with the semaphore. Applications using semaphores for synchronisation usually start with this value set to 0, while applications that use semaphores for resource management start with this value equal to the number of resources.

The C++ API is:

std::size_t value = sem.initial_value();

The C API is:

size_t value = os_semaphore_get_initial_value(&sem);

Real-world applications may include monitoring mechanisms to detect erroneous conditions. Recovering from such conditions may require to return the semaphore to stable state; µOS++ provides a function to return the semaphore to the initial state after construction.

The C++ API is:

sem.reset();

The C API is:

os_semaphore_reset(&sem);

In C++, if the semaphores were created using the normal way, the destructors are automatically invoked when the current block exits, or, for the global semaphores instances, after the main() function returns. Semaphores created with placement new need to be destructed manually.

In C, all semaphores must be destructed by explicit calls to os_semaphore_destruct().

There should be no threads waiting on the semaphore when it is destroyed, otherwise an assert check will trigger.

Originally semaphores were used to control access to shared resources, for example to I/O devices.

The classical example includes two or more threads writing messages to an I/O port. Without any control mechanism, the characters from one thread messages might get intermingled with characters from other thread messages.

The solution is to add a mechanism that allows one thread to gain exclusive access to the device and prevent other threads to write characters before the message is fully transferred. Such a critical section may use a binary semaphore, initialised to 1, and brace writing messages with wait() and post() calls.

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 1.

semaphore_binary sem { "sem", 1 };

void

write_message(const char* msg)

{

// Wait until no other thread is using the device and lock access to it.

sem.wait();

// Write the message, one character at a time, without fear

// that other threads will intervene.

while (*msg)

{

write_char(*msg);

++msg;

}

// Unlock access to the device.

sem.post();

}

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

// Global static global storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sem;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 1.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sem, "sem", 1);

// ...

os_semaphore_destruct(&sem);

return 0;

}

void

write_message(const char* msg)

{

// Wait until no other thread is using the device and lock access to it.

os_semaphore_wait(&sem);

// Write the message, one character at a time, without fear

// that other threads will intervene.

while (*msg)

{

write_char(*msg);

++msg;

}

// Unlock access to the device.

os_semaphore_post(&sem);

}

**

It is mandatory for the binary semaphore to be initialised with 1 (i.e. device available) for the first wait() to not block.

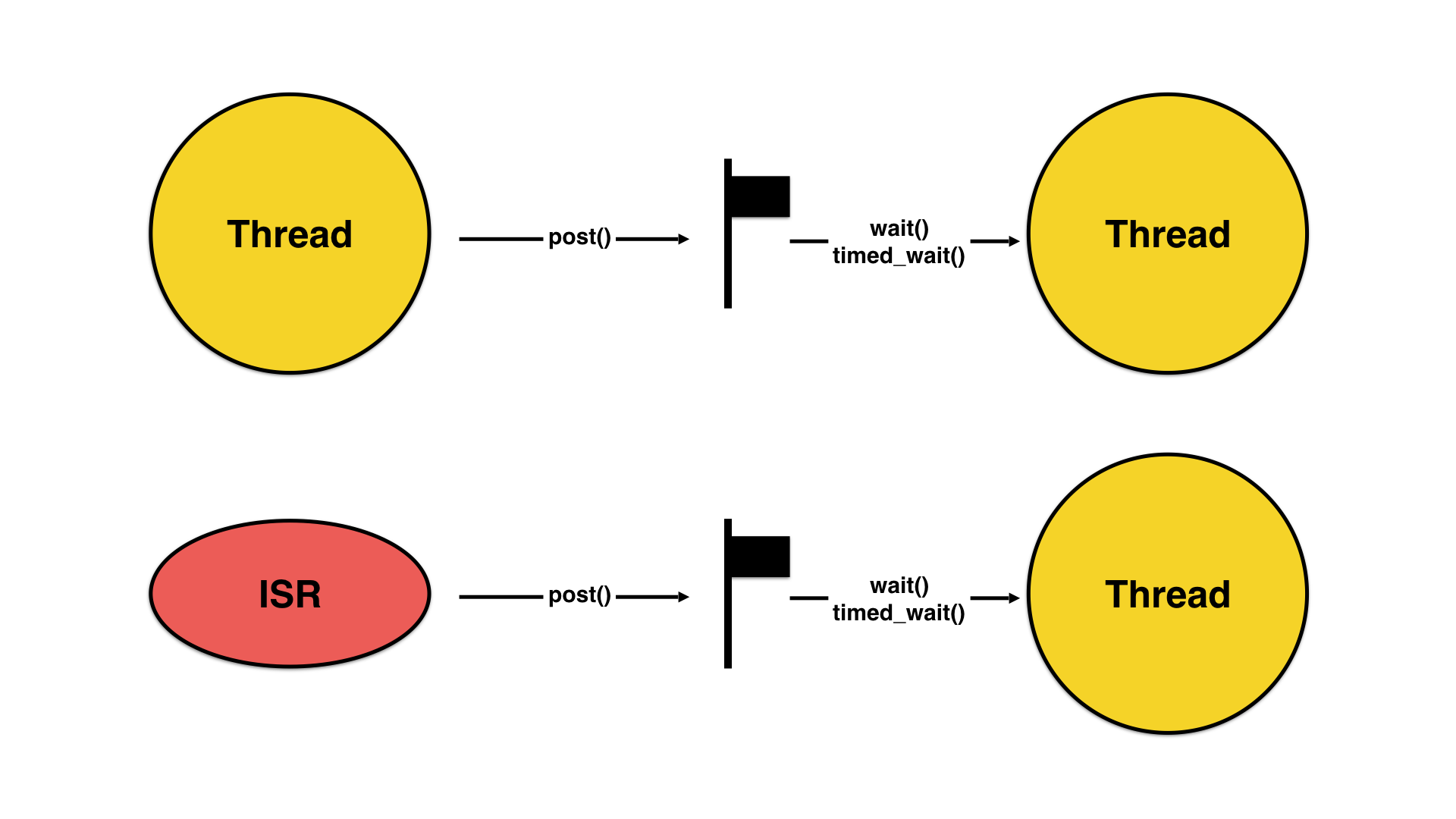

It is common for a thread to wait for event generated by an ISR (or another thread). In this case, no data needs to be exchanged, only the fact that the ISR or the thread (on the left) has occurred is important. Using a semaphore for this type of synchronization is called a unilateral rendezvous.

Unilateral rendezvous

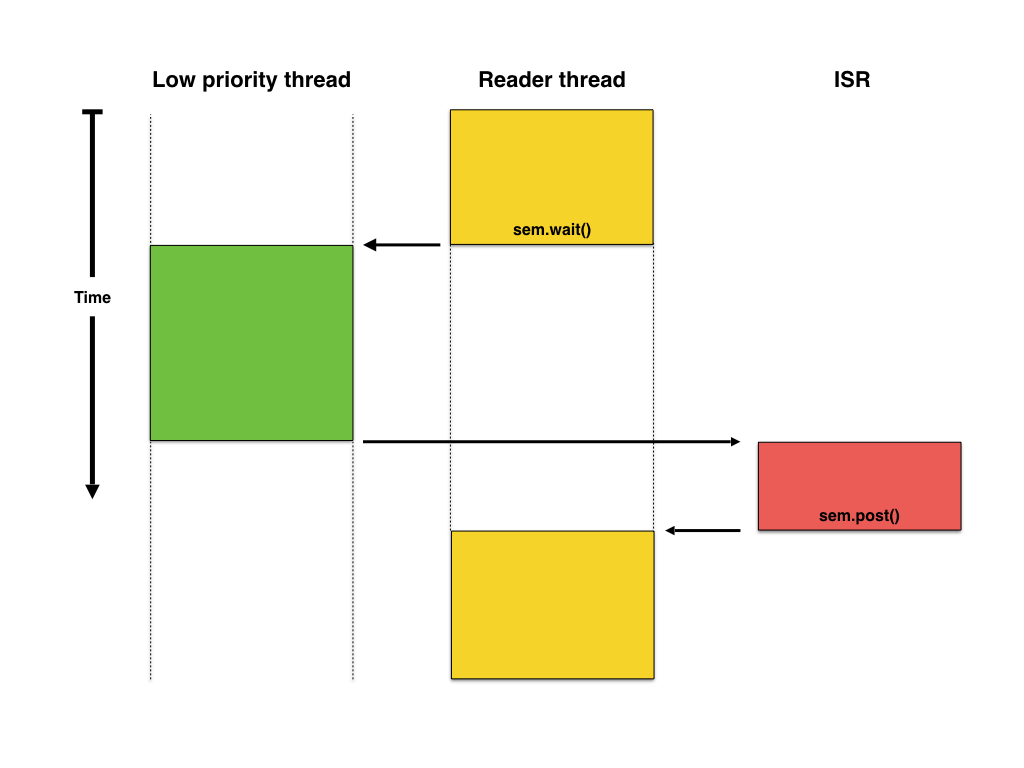

A unilateral rendezvous is used when a thread initiates an I/O operation and waits (i.e., calls wait()) for the semaphore to be posted. Lower priority threads are executed. When the I/O operation is complete, an ISR (or another thread) signals the semaphore (i.e., calls post()), and the thread is resumed.

Unilateral rendezvous timeline

An example code in C++ is:

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 0.

semaphore_binary sem { "sem", 0 };

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Not much to do, the semaphore was created by the static

// constructors, before entering main().

return 0;

}

static volatile uint8_t device_byte;

uint8_t

read_byte(void)

{

// Wait until the semaphore is posted.

sem.wait();

return device_byte;

}

void

device_interrupt_service_routine(void)

{

// Store the device data in a static location.

device_byte = read_device_register();

// Inform the reader that new data is available.

sem.post();

}

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

// Global static global storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sem;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 0.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sem, "sem", 0);

// ...

os_semaphore_destruct(&sem);

return 0;

}

static volatile uint8_t device_byte;

uint8_t

read_byte(void)

{

// Wait until the semaphore is posted.

os_semaphore_wait(&sem);

return device_byte;

}

void

device_interrupt_service_routine(void)

{

// Store the device data in a static location.

device_byte = read_device_register();

// Inform the reader that new data is available.

os_semaphore_post(&sem);

}

This example is for demonstrative purposes only. A real-world example would probably need to use a circular buffer to store multiple bytes, to avoid loosing data when multiple interrupts occur before the read_byte() is called.

Semaphores are great synchronisation objects, especially with events occurring on interrupts.

However semaphores are subject to several problems, which must be known and addressed during system design.

When using the semaphores for managing common resources, it is absolutely mandatory to begin the critical section with wait() and to end it with post(). Any possibility to leave the critical section in the middle of it (via return, break, continue, goto, etc) will result in a deadlock and should be avoided.

Recursive deadlock can occur if a thread tries to lock a semaphore it has already locked. This can typically occur in libraries or recursive functions.

A typical scenario is to have a functional program, like the one protecting the write_message() function and try to “improve” it to protect a series of messages:

/// @file app-main.cpp

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os.h>

using namespace os;

using namespace os::rtos;

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 1.

semaphore_binary sem { "sem", 1 };

void

write_message(const char* msg)

{

// Wait until no other thread is using the device and lock access to it.

sem.wait();

// Write the message, one character at a time, without fear

// that other threads will intervene.

while (*msg)

{

write_char(*msg);

++msg;

}

// Unlock access to the device.

sem.post();

}

// ...

void

write_many_messages(void)

{

sem.wait();

write_message("one");

write_message("two");

write_message("three");

sem.post();

}

A similar example, but written in C:

/// @file app-main.c

#include <cmsis-plus/rtos/os-c-api.h>

// Global static global storage for the semaphore object instance.

os_semaphore_t sem;

int

os_main (int argc, char* argv[])

{

// ...

// Create a binary semaphore, with the initial count as 1.

os_semaphore_binary_construct(&sem, "sem", 1);

// ...

os_semaphore_destruct(&sem);

return 0;

}

void

write_message(const char* msg)

{

// Wait until no other thread is using the device and lock access to it.

os_semaphore_wait(&sem);

// Write the message, one character at a time, without fear

// that other threads will intervene.

while (*msg)

{

write_char(*msg);

++msg;

}

// Unlock access to the device.

os_semaphore_post(&sem);

}

void

write_many_messages(void)

{

os_semaphore_wait(&sem);

write_message("one");

write_message("two");

write_message("three");

os_semaphore_post(&sem);

}

Well… bad idea! Since the semaphore was created as binary, the first wait() in write_many_messages() will lock it, and the inner wait() in write_message() will find it locked and block forever.

For such scenarios, recursive mutexes are definitely more appropriate.

What if a thread that locked a semaphore is terminated? Since the semaphore does not keep track of its owner, most implementations are not able to detect this and all thread waiting (or may wait in the future) will never acquire the semaphore and deadlock. To partially address this, it is recommended to use the timed_wait(), which specifies a timeout.

Semaphores are subject to a serious problem in real-time systems called priority inversion, where a high priority thread becomes delayed for an indefinite period by a low priority thread, preventing it to meet its deadlines. A very high profile case was the NASA JPL’s Mars Pathfinder spacecraft (see What really happened on Mars?)

One of the best solutions to prevent priority inversion is to use mutexes with priority inheritance.

If using semaphores for mutual exclusion is problematic, using them for synchronisation is fine, and the the typical scenario is unilateral rendezvous. However, for this to work, the semaphore must be created with an initial count value of 0 (zero).