|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

| Last modified on Sat Jul 22 11:30:02 2023 UTC. | Improve this page |

From the software point of view, an embedded system is a small computer, built for a dedicated function (as opposed to general purpose computers).

There are many types of embedded systems, with varying degrees of complexity, from small proximity sensors used in home automation, to internet routers, remote surveillance cameras and even smart phones.

Complex systems, especially those with high bandwidth communication needs, are designed around embedded versions of GNU/Linux, which include a large kernel, a root file system, multiple processes, not very different from their larger cousins running on desktop computers.

The application is generally a combination of processes running in user space, and device drivers, running inside the kernel.

Smaller devices have much less resources, and are build around microcontrollers which do not have the required hardware to properly run an Unix kernel.

In this case the application is monolithic and runs directly on the hardware, thus the name bare-metal.

µOS++ focuses on these bare-metal applications, especially those running on ARM Cortex-M devices. Although µOS++ can be ported on larger ARM Cortex-A cores, even the 64-bits ones, there are no plans to include support for MMU, virtual memory, separate processes and other such features specific to the Unix world.

A real-time embedded system is a piece of software that manages the resources and the time behaviour of an embedded device, usually build around a microcontroller, emphasising on the correctness of the computed values and their availability at the expected time.

µOS++ is a real-time operating system (RTOS).

There are two types of real-time systems, hard and soft real-time systems.

The main difference between them is determined by the consequences associated with missing deadlines. Obtaining correctly computed values but after the deadline has passed may range from useless to dangerous.

For hard real-time systems the tolerance to missing deadlines is very low, since missing a deadline often results in a catastrophe, which may involve the loss of human lives.

For soft real-time systems this tolerance is not as tight, since missing deadlines is generally not as critical.

Absolute hard real-time systems, with near zero tolerance, are typically very difficult to design, and it is recommended to approach them with caution.

However, with a careful design, reasonable tolerance can be obtained, and µOS++ can be successfully used in real-time applications.

Legal-notice: According to the MIT license, “the software is provided as-is, without warranty of any kind”. As such, its use in life threatening applications should be avoided.

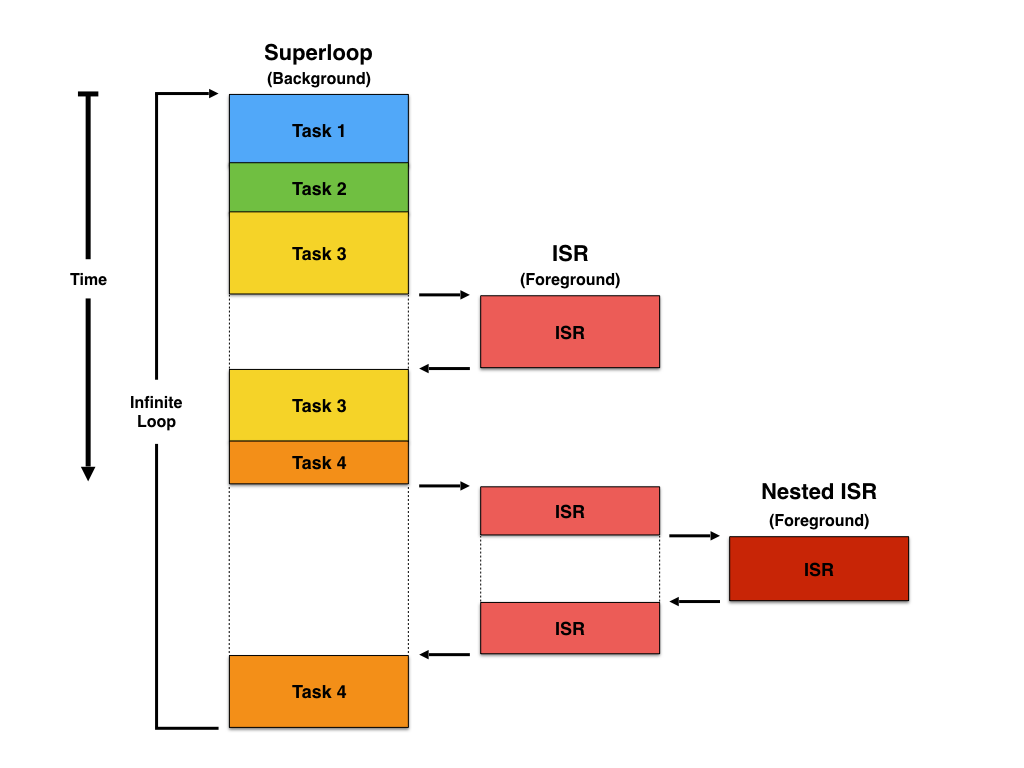

There are many techniques for writing embedded software. For low complexity systems, the classic way does not use an RTOS, but are designed as foreground/background systems, or superloops.

An application consists of an infinite loop that calls one or more functions in succession to perform the desired operations (background).

Interrupt service routines (ISRs) are used to handle the asynchronous, real-time parts of the application (foreground).

In this architecture, the functions implementing the various functionalities are inherently, even if not formally declared as such, some kind of finite state machines, spinning around and switching states based on inputs provided by the ISRs.

Superloop application

The superloop technique has the advantage of requiring only one stack and sometimes may result in simpler applications, especially when the entire functionality is performed on ISRs, and the background logic is reduced to an empty loop waiting for interrupts.

However, for slightly more complex applications, expressing the entire logic as a set of state machines is not easy, and maintenance becomes a serious problem as the program grows.

The overall reaction speed may also be a problem, since the delay between the moment when the ISR makes available the input and the moment when the background routine can use it is not deterministic, depending on many other actions that can happen at the same time in the superloop.

To ensure that urgent actions are performed in a timely manner, they must be moved on the ISRs, lengthening them and further worsening the reaction speed of the application.

Regardless how elaborate the techniques for implementing the finite state machines are, the human mind still feels more comfortable with linear representations of lists of steps to be done, than with graph and state tables.

In the µOS++ context, a task is a well defined sequence of operations, usually represented in a programming language as a function.

A complex application can be decomposed as a series of tasks, some executed in succession, some executed in parallel and possibly exchanging data.

Multi-tasking is the technique of running multiple tasks in parallel.

The Java Threads book (one of the inspiration source for the early versions of this project) states:

Historically, threading was first exploited to make certain programs easier to write: if a program can be split into separate tasks, it’s often easier to program the algorithm as separate tasks or threads… while it is possible to write a single-threaded program to perform multiple tasks, it’s easier and more elegant to place each task in its own thread.

Threads and processes are the operating system mechanisms for running multiple tasks in parallel.

The main difference between threads and processes is how the memory space is organised. Processes run in separate, virtual memory spaces, while threads share a common memory space.

The implementation of virtual memory requires hardware support for a MMU, available only in application class processors, like the Cortex-A devices.

Smaller devices, like the ARM Cortex-M devices, can still run multiple tasks in parallel, but, without a MMU and the benefits of virtual memory, these multiple tasks are performed by multiple threads, all sharing the same memory space.

As such, µOS++ is a multi-threaded system, supporting any number of threads, with the actual number limited only by the amount of available memory.

One of the most encountered scenario when implementing tasks, is to wait for some kind of input data, for example by performing a read(), then process the data and, most of the times, repeat this sequence in a loop. When the system executes the read() call, the thread might need to wait for the required data to become available before it can continue to the next statement. This type of I/O is called blocking I/O: the thread blocks until some data is available to satisfy the read() function.

One possible implementation is to loop until the data becomes available, but this type of behaviour simply wastes resources (CPU cycles and implicitly power) and should be avoided by all means.

Well behaved applications should never enter (long) busy loops waiting for conditions to occur, but instead suspend the thread and arrange for it to be resumed when the condition is met. During this waiting period the thread completely releases the CPU, so the CPU will be fully available for the other active threads.

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that the only exception to the rule applies to short delays, where short means delays with durations comparable with the multitasking overhead required to suspend/resume threads (where the context switching time plays an important role). On most modern microcontrollers this is usually in the range of microseconds.

As seen before, at thread level, the goal is to process the available data as soon as possible and suspend itself to wait for more data. In other words, the thread ideal way of life should be… to do nothing!

But what happens if all threads accomplish this goal and there is nothing else to do?

Well, enter the idle thread. This internal thread is always created before the scheduler is started; it has the lowest possible priority, and is always running when there are no more other threads to run.

The idle thread can perform various low priority maintenance chores (like destroying terminated threads), but at a certain moment even the idle thread will have nothing else to do.

When the idle thread has nothing to do, it still can do something useful: it can put the CPU to a shallow sleep, and wait for the next interrupt (the Cortex-M devices use the Wait For Interrupt instruction for this).

In this mode the CPU is fully functional, with all internal peripherals active, but it does not run any instructions, so it is able to save a certain amount of power.

If the application has relatively long inactive moments, further savings are possible, i.e. power down all peripherals except a low frequency real time timer, usually triggered once a second. In this case the idle task can arrange for the CPU to enter a deep sleep mode, saving a significantly higher amount of power.

As a summary, the multilevel strategy used to reduce power consumption implies:

In conclusion, by using a wide range of power management techniques, an RTOS can be successfully used in very low power applications.

Running multiple threads in parallel is only apparent, since under the hood the threads are decomposed in small sequences of operations, serialised in a certain order, on the available CPU cores. If there is only one CPU core, there is only one running thread at a certain moment. The other threads are suspended, in a sense are frozen and put aside for later use; when the conditions are again favourable, each one may be revived and, for a while, allowed to use the CPU.

Suspended threads are sometimes called sleeping, or dormant; these terms are also correct, but it must be clearly understood that the thread status is only a software status, that has nothing to do with the CPU sleep modes, which are hardware related; the existence of suspended threads means only that the threads are not scheduled for execution; they do not imply that the CPU will enter any of the sleep modes, which may happen only when all threads are suspended.

Restarting a suspended thread requires restoring exactly the internal CPU state existing at the moment when the thread was suspended. Physically, this state is usually stored in a certain number of CPU registers. When the thread is suspended, the content of these registers must be stored in a separate RAM area, specific to each thread. When the thread is resumed, the same registers must be restored with the saved values.

This set of information required to resume a thread is also called the thread execution context, in short the context.

The set of operations required to save the context of the running thread, select the next thread and restore its context is called context switching.

Modern CPUs, like the ARM Cortex-M devices, make use of a stack to implement nested function calls and local function storage.

The same stack can be used to store the thread context. When starting a context switch all registers are pushed onto the thread stack. Then the resulting stack pointer is saved in the thread context area. Resuming a thread is done in reverse order, i.e. the stack pointer is retrieved from the thread context, all registers are popped from the stack and execution is resumed.

This mechanism usually simplifies the scheduler implementation; it is used in the Cortex-M port of the µOS++ scheduler.

Historical note: early microcontrollers, like PIC before the 18 series, did not have a general purpose stack; instead they had a limited call stack, allowing only a small number of nested calls.

The most frequent reason for a context switch is when a thread decides to wait for a resource that is not yet available, like a new character from a device, a message in a queue, a mutex protecting a shared resource, etc.

In this case, yielding the CPU from one thread to another is done implicitly by the system function called to wait for the resource.

In case of long computations, a well behaved thread would not hold the CPU for the entire computation period, but explicitly yield the CPU from time to time, to give other threads a chance to run.

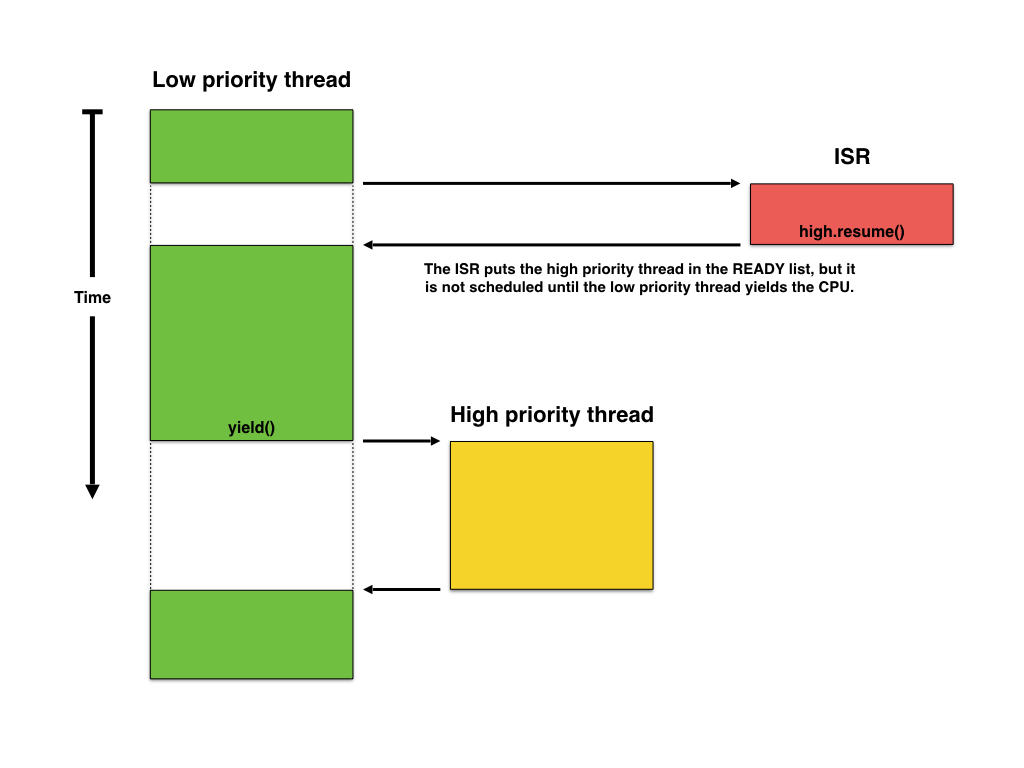

This polite behaviour, when the switch is performed by the thread itself, is called cooperative multi-tasking, since it depends on a the good-will of all tasks running in parallel.

The biggest disadvantage of cooperative multi-tasking is a possible low reaction speed, for example when an interrupt wants to resume a high priority thread, this might not happen until the low priority thread decides to yield.

Cooperative context switching.

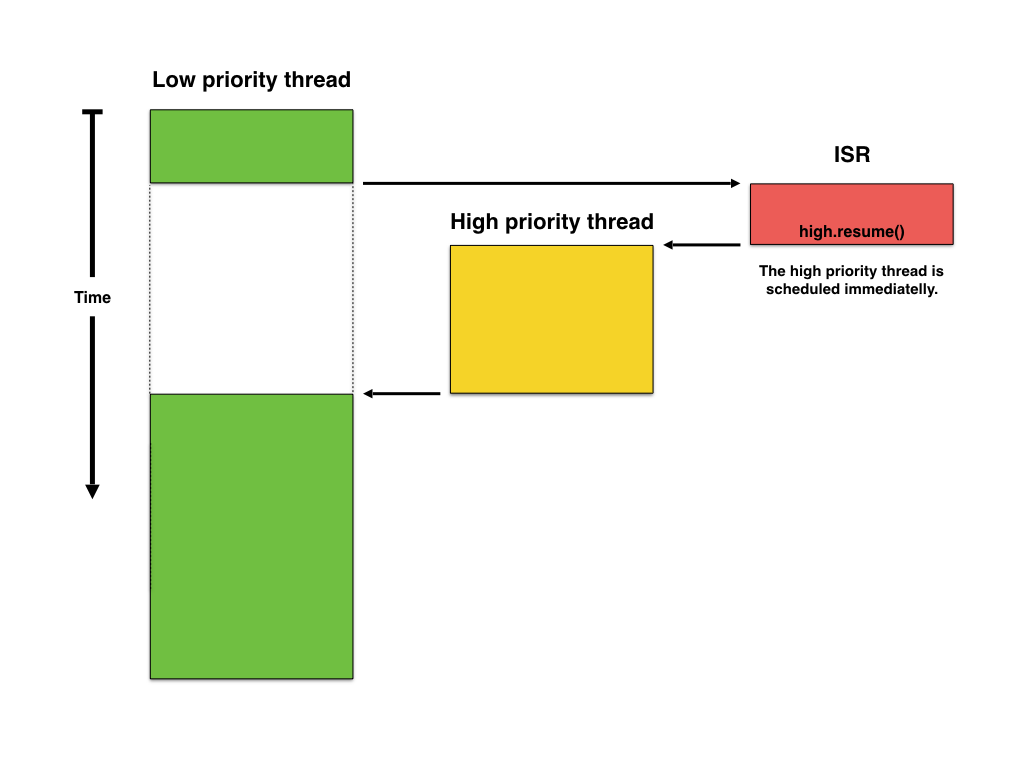

In this case the solution is to allow the interrupt to trigger a context switch from the low priority thread to the high priority thread without the threads event knowing about. This automatic kind of context switch is also called preemptive multi-tasking, since long running threads are preempted to hog the CPU in favour of higher priority threads.

Preemptive context switching

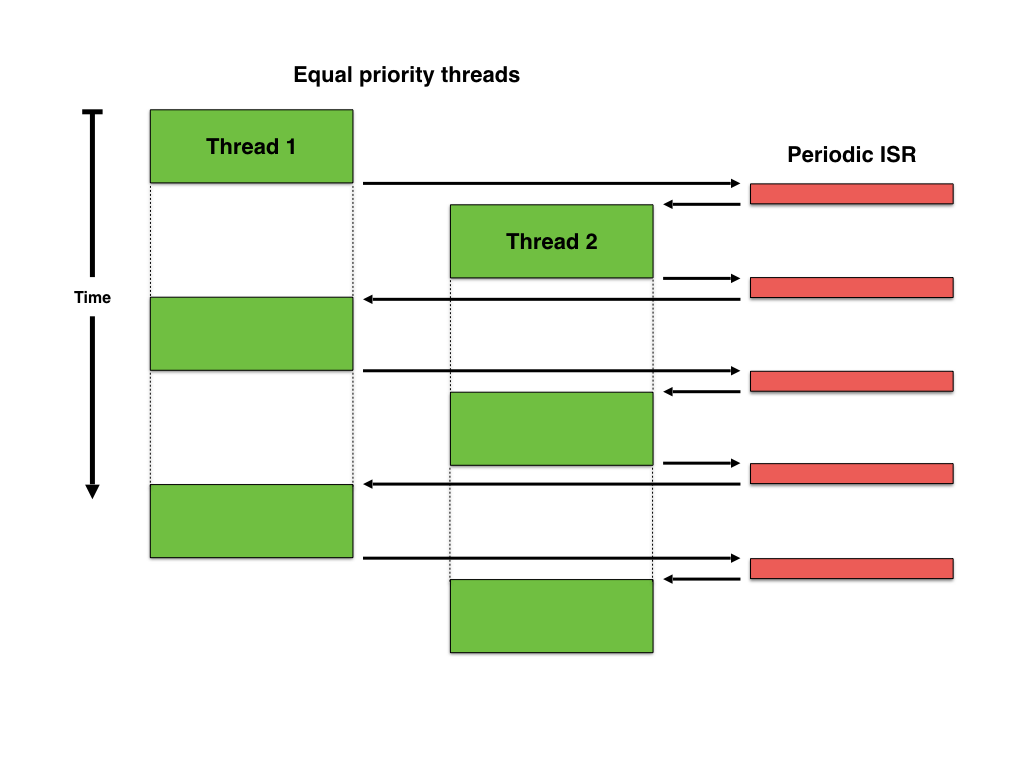

Once the mechanism for an interrupt to preempt a thread is functional, a further improvement can be added: a periodic timer (for example the timer used to keep track of time), can be used to automatically preempt threads and give a chance to equal priority threads to alternatively get the CPU.

Preemptive context switching with periodic timer

In general cooperative multitasking is easier to implement, and, since the CPU is released under the application control, inter-thread synchronisation race conditions are avoided. However, at a more thorough analysis, this is not necessarily a feature, but a subtle way to hide other application synchronisation bugs, like the lack of explicit critical sections. In other words, a well behaved application should protect a shared resource by use of a critical section anyway, since although another task cannot execute inside another task, interrupt service routines can, and without the critical section it is very likely that a race condition may occur.

One special useful application of the cooperative mode is for debugging possible inter-thread race conditions. In case of strange behaviours that might be associated with synchronisation problems, if disabling preemption solves the problem, then an inter-thread race condition is highly probable. It the problem is still present in cooperative mode, than most probably the race condition involves the interrupt service routines. In both cases, the cure is to use critical sections where needed.

µOS++ implements both cooperative and preemptive multi-tasking.

Most schedulers keep track of time, at least for handling timeouts. Technically this is implemented with a periodic hardware timer, and timeouts are expressed in timer ticks.

A common frequency for the scheduler timer is 1000 Hz, which gives a resolution of 1 ms for the scheduler derived clock.

For preemptive schedulers, the same timer can be used to trigger context switches.

Acknowledging the importance of a system timer, ARM defined SysTick as a common timer for Cortex-M devices, which makes it a perfect match for the scheduler timer.

In real life applications, there are cases when some threads, for various reasons, must be interrupted.

µOS++ threads include support for interruption, but this support is cooperative, i.e. threads that might be interrupted should check for interruption requests and quit inner loops in an ordered manner.

A thread control block (TCB) is a data structure used by the scheduler to maintain information about a thread. Each thread requires its own TCB.

Being implemented in a structured, object oriented language like C++, the µOS++ threads implicitly have instance data structures associated with the objects, which are functionally equivalent to common TCBs; in other words, the µOS++ TCBs are the actual thread instances themselves.

The thread internal variables are protected, and cannot be directly accessed from user code, but for all relevant members there are public accessor and mutator functions defined.

The mechanism that performs the context switches is also called scheduling, and the code implementing this mechanism is also called scheduler.

During their lifetime, threads can be in different states.

Apart from some states used during thread creation and destruction, the most important thread states are:

To performs its duties efficiently, the scheduler needs to keep track only of the threads ready to run. Threads that for a little while must wait for various events can be considered to momentarily exit the scheduler jurisdiction, and other mechanisms, like timers, synchronisation objects, notifications, etc are expected to return them to the scheduler when ready to run.

In order to keep track of the ready threads, the scheduler maintains a ready list. The term list is generic, regardless of the actual implementation, which might be anything from a simple array to multiple double linked lists.

The main existential question in the life of a scheduler is how to select the next thread to run among the treads in the READY list? This question is actually much more difficult to answer when dealing with a hard real-time application, with strict life or death deadlines for threads.

Legal notice: From this point of view it must be clearly stated that the µOS++ scheduler does not guarantee any deadlines in thread executions.

However, what the µOS++ scheduler does, is to be as fair as possible with existing threads, and give them the best chance to access the CPU.

One of the simple ways to manage the ready list is FIFO, with new threads inserted at the back, and the scheduler extracting from the front. This mechanism works well if there is no need to guarantee response time.

When response time becomes important, the mechanism can be greatly improved by assigning priorities to threads, and ordering the ready list by priorities.

By always inserting higher priority threads immediately in front of the lower priority ones, two goals are achieved at the same time:

By default, the µOS++ user threads are created with normal priority. As the result, the scheduler default behaviour is round-robin.

As soon as thread priorities are changed, the scheduler behaviour automatically changes to priority scheduling, falling back to round-robin for threads with equal priorities.

As a general rule, threads that implement hard real-time functions should be assigned priorities above those that implement soft real-time functions. However, other characteristics, such as execution times and processor utilization, must also be taken into account to ensure that the entire application will never miss a hard real-time deadline.

One possible technique is to assign unique priorities, in accordance with the thread periodic execution rate (the highest priority is assigned to the thread that has the highest frequency of periodic execution). This technique is called Rate Monotonic Scheduling (RMS).

Priority inversion is a problematic scenario in scheduling in which a high priority thread is indirectly prevented to run by a lower priority thread effectively “inverting” the relative priorities of the two threads.

The first scenario is the following:

Although for the high priority thread this is an unfortunate scenario, there is not much that it can do but wait for the low priority thread to release the resource.

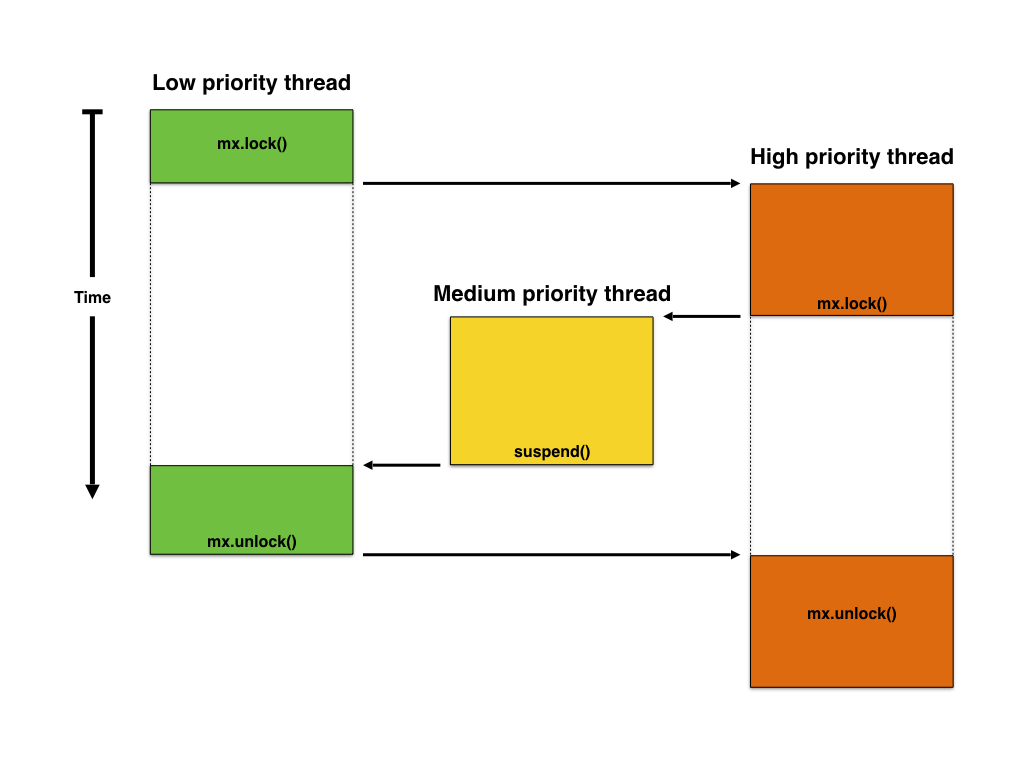

An even more unfortunate scenario is the following:

Priority inversion

The problem in this scenario is that although the high priority thread announced its intention to acquire the resource and knows it must wait for the low priority thread to release it, a medium priority thread can still prevent this to happen, behaving as like having the highest priority. This is known as unbounded priority inversion. It is unbounded because any medium priority can extend the time the high priority thread has to wait for the resource.

This problem was known for long, but many times ignored, until it was reported to have affected the NASA JPL’s Mars Pathfinder spacecraft (see What really happened on Mars?).

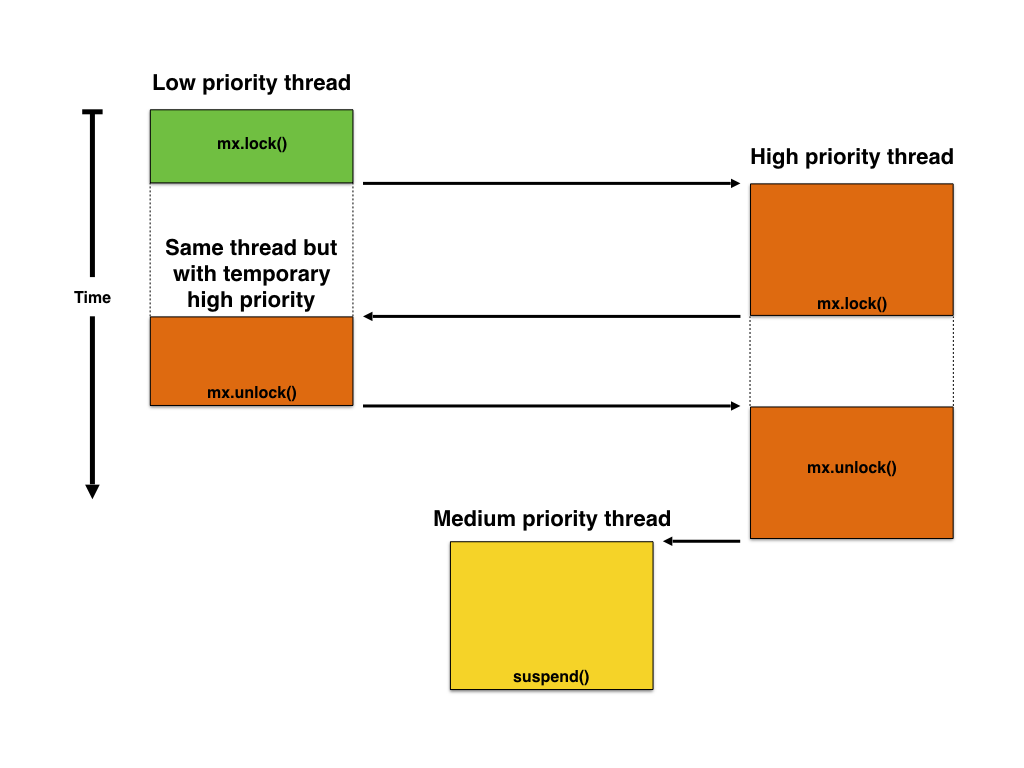

One of the possible solutions to avoid this is for the high priority thread to temporarily boost the priority of the low priority thread, to prevent other threads to interfere and so help the low priority thread to complete its job sooner. This is known as priority inheritance.

Priority inheritance

To be noted that priority inheritance does not completely fix the priority inversion problem, the high priority thread still has to wait for the low priority thread to release the resource, but at least it does its best to prevent other middle priority threads to interfere. It is not a good practice to rely only on priority inheritance for correct system operation and the problem should be avoided at system design time, by considering how resources are accessed.

In a multi-tasking application, the threads and the ISRs are basically separate entities. However, in order to achieve the application’s goals, they must work together and exchange information in various ways.

The easiest way to communicate between different pieces of code is by using global variables. In certain situations, it can make sense to communicate via global variables, but most of the time this method has disadvantages.

For example, if you want to synchronize a thread to perform some action when the value of a global variable changes, the thread must continually poll this variable, wasting precious computation time and energy, and the reaction time depends on how often you poll.

A better way is to suspend the waiting thread and, when the expected event occurs, to resume it. This method requires a bit of support from the system, to manage the operations behind suspend/resume, but has the big advantage that a suspended thread does not waste computation time and energy.

A message queue is usually an array of structures accessed in a FIFO way. Threads or ISRs can send messages to the queue, and other threads or interrupts can consume them.

Threads can block while waiting for messages, and as such do not waste CPU cycles.

Semaphores, and especially binary semaphores, are commonly used to pass notifications between different parts of the code, mostly from ISRs to threads. However, they have a richer semantic, especially the counting semaphores, and can also be used to keep track of the number of available resources (for example total positions in a circular buffer), which somehow places them at the border with managing shared resources.

An event flag is a binary variable, representing a specific condition that a thread can wait for. When the condition occurs, the flag is raised and the thread is resumed.

Multiple flags can be grouped and the thread can be notified when all or any of the flags was raised.

A shared resource is typically a variable (static or global), a data structure, table (in RAM), or registers in an I/O device, accessed in common by different parts of the code.

Typical examples are lists, memory allocators, storage devices, that all need a specific method to protect against concurrent accesses.

The technique for obtaining exclusive access to shared resources is to create critical sections, which temporarily lock access.

When the resource is also accessed from ISRs, the usual solution to prevent an ISR to access the resource at the same time with a thread or another lower priority ISR, is to temporarily disable the interrupts while using the shared resource.

The overhead to disable/enable interrupts is usually low, and for some devices, like the Cortex-M[347] ones, it is even possible to disable interrupts only partially, from a given priority level down, keeping high priority interrupts enabled.

Although apparently simple, this technique is often misused in cases of nested critical sections, when the inner critical section inadvertently enables interrupts, leading to very hard to trace bugs. The correct and bullet proof method to implement the critical sections is to always save the initial interrupt state and restore it when the critical section is exited.

This method must be used with caution, since keeping the interrupts disabled too long impacts the system responsiveness.

Typical resources that might be protected with interrupts critical sections are circular buffers, linked lists, memory pools, etc.

If the resource is not accessed from ISRs, a simple solution to prevent other threads to access it is to temporarily lock the scheduler, so that no context switches can occur.

Locking the scheduler has the same effect as making the task that locks the scheduler the highest-priority task.

Similar to interrupts critical sections, the implementation of scheduler critical sections must consider nested calls, and always save the initial scheduler state and restore it when the critical section is exited.

This method must be used with caution, since keeping the scheduler locked too long impacts the system responsiveness.

Counting semaphores can be used to control access to shared resources used on ISRs, like circular buffers.

Since they may be affected by priority inversions, their use to manage common resources should be done with caution.

This is the preferred method for accessing shared resources, especially if the threads that need to access a shared resource have deadlines.

µOS++ mutexes have a built-in priority inheritance mechanism, which avoids unbound priority inversions.

However, mutexes are slightly slower (in execution time) than semaphores since the priority of the owner may need to be changed, which requires more CPU processing.

A semaphore should be used when resources are shared with an ISR.

A semaphore can be used instead of a mutex if none of the threads competing for the shared resource have deadlines to be satisfied.

However, if there are deadlines to meet, you should use a mutex prior to accessing shared resources. Semaphores are subject to unbounded priority inversions, while mutexes are not. On the other hand, mutexes cannot be used on interrupts, since they need an owner thread.

A deadlock, also called a deadly embrace, is a situation in which two threads are each unknowingly waiting for resources held by the other.

Consider the following scenario where thread A and thread B both need to acquire mutex X and mutex Y in order to perform an action:

At the end of this scenario, thread A is waiting for a mutex held by thread B, and thread B is waiting for a mutex held by thread A. Deadlock has occurred because neither thread can proceed.

As with priority inversion, the best method of avoiding deadlock is to consider its potential at design time, and design the system to ensure that deadlock cannot occur.

The following techniques can be used to avoid deadlocks:

Most system objects are self-contained, and the rule is that if the storage requirements are known, constant and identical for all instances, then the storage is allocated in the object instance data.

However some system objects require additional memory, different from one instance to the other. Examples for such objects are threads (which require stacks), message queues and memory pools.

This additional memory can be allocated either statically (at compile-time) or dynamically (at run-time).

By default, all base classes use the system allocator to get memory.

In C++ all such classes are doubled by templates which handle allocation.

Another solution, also available to the C API, is to pass user defined storage areas via the attributes used during object creation.

For all objects that might need memory, µOS++ uses the system allocator os::rtos::memory::allocator<T>, which by default is mapped to an allocator that uses the standard new/delete primitives, allocating storage on the heap.

This allocator is a standard C++ allocator. The user can define another such standard allocator, and configure the system allocator to use it, thus customising the behaviour of all system objects.

Even more, system objects that need memory are defined as templates, which can be parametrised with an allocator, so, at the limit, each object can be constructed with its own separate allocator.

The biggest concern with using dynamic memory is fragmentation, a condition that may render a system unusable.

To be noted that internally µOS++ does not use dynamic allocation at all, so if the application is careful enough not to use objects that need dynamic allocation, the resulting code is fully static.

Most application handle time by using the scheduler timer.

However low power applications opt to put the CPU in a deep sleep, which usually powers down most peripherals, including the scheduler timer.

For these situations a separate low power real-time clock is required; powered by a separate power source, possibly a battery, this clock runs even when the rest of the device is sleeping.

This clock not only keeps track of time, it can also trigger interrupts to wakeup the CPU at desired moments.

The usual resolution of the real-time clock is 1 sec.

Many authors also refer to their RTOSes as “kernels”. Well, even if OS in RTOS stands for operating system, this definition is somehow stretched to the limit, since in bare-metal embedded systems the so called operating system is only a collection of functions handling thread switching and synchronisation, linked together with the application in a monolithic executable.

As such, the term kernel is even more inappropriate, since there is no distinct component to manage all available resources (memory, CPU, I/O, etc) and to provide them to the application in a controlled way; most of the time the application has full control over the entire memory space, which, for systems with memory mapped peripherals, also means full control over the I/O.

The only kernel specific function available in bare-metal embedded systems is CPU management; with multiple threads sharing the CPU, probably a more appropriate name for the RTOS core component is scheduler; the µOS++ documentation uses the term operating system in its definition, occasionally refers to itself as a scheduler, and explicitly tries to avoid the term kernel.

Many authors refer to threads as “tasks”. Strictly speaking, threads (together with processes) are the system primitives used to run multiple tasks in parallel in a multitasking system.